Few artists carry truth in their voice the way Obongjayar does. Every word feels lived-in - drawn from somewhere deep and beautifully human.

Raised in Calabar, Nigeria, before moving to London as a teenager, his sound is a fearless collision of worlds - global pop melodies rooted in West African rhythm, charged with punk energy and a poet’s soul. The result is music that feels both ancestral and futuristic; grounded yet limitless.

It’s this magnetism that’s drawn collaborators like Little Simz, Danny Brown, Jeshi, and Afrobeats architect Sarz - and earned him a Top 5 hit with Fred again..’s “adore u”, built around Obongjayar’s haunting original “I Wish It Was Me.” His debut album Some Nights I Dream of Doors was a critical triumph, landing him an Ivor Novello nomination and cementing his place as one of the UK’s most singular modern storytellers.

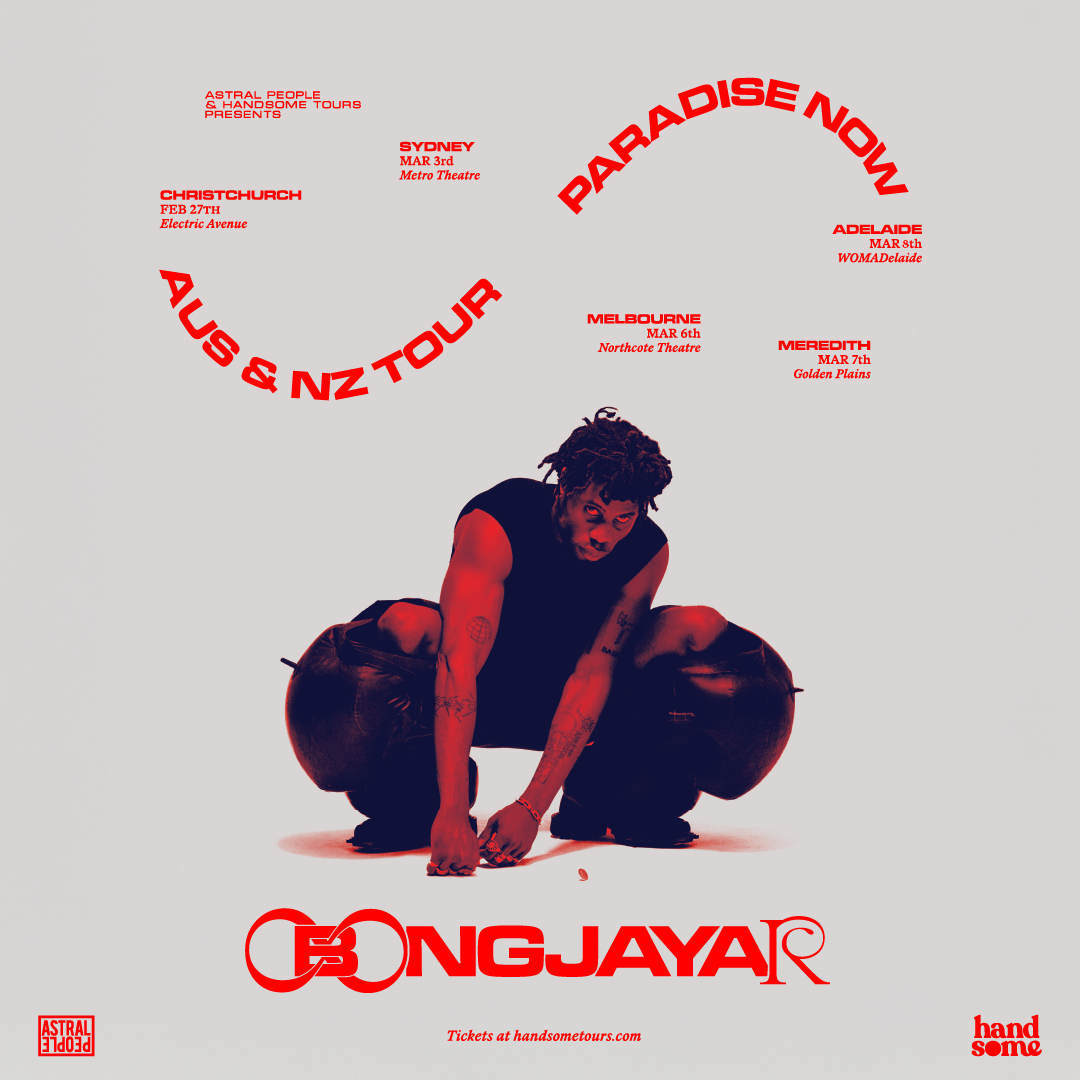

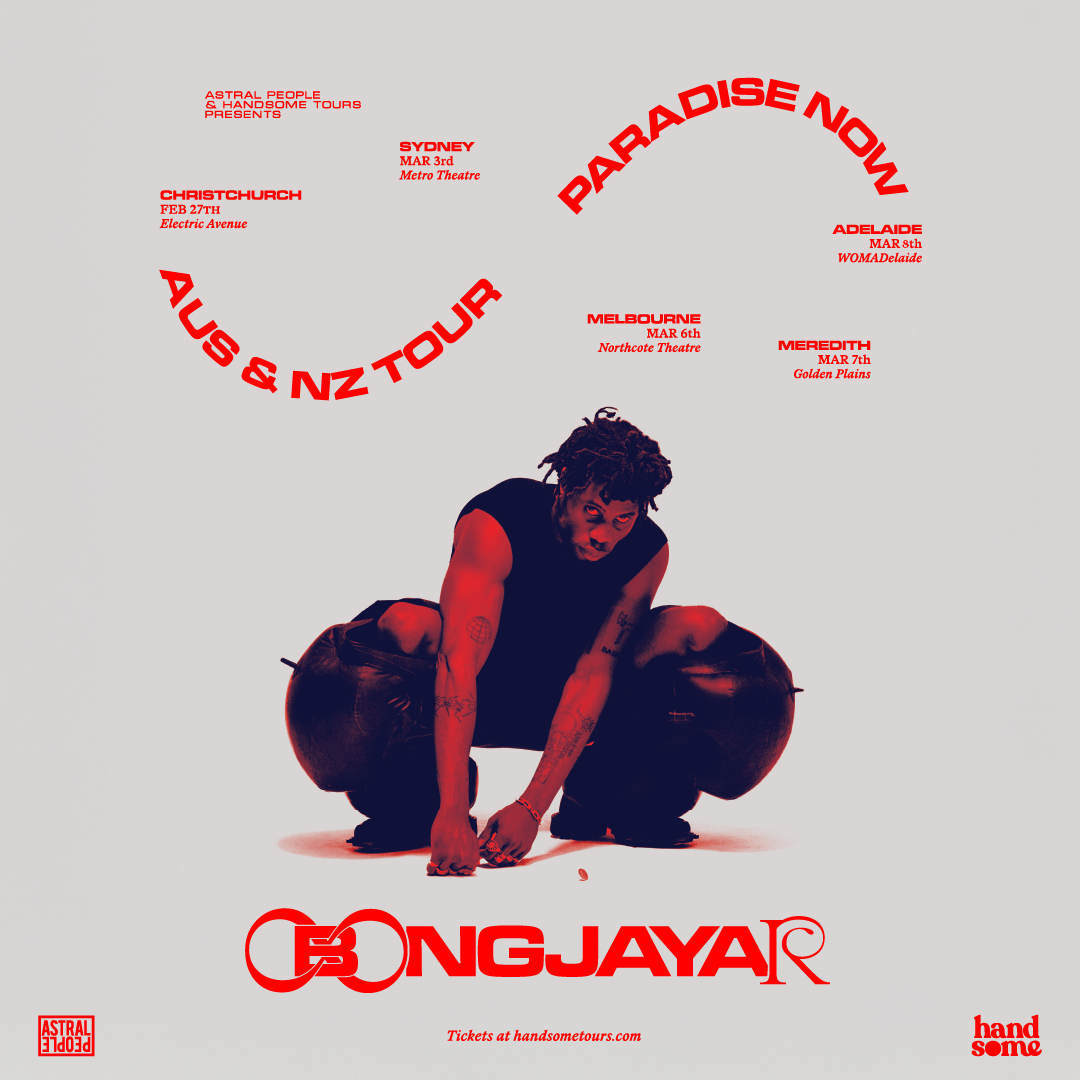

Now, he brings that unmistakable voice - and electric presence - back to Australia and New Zealand. Hitting major festivals including Golden Plains, WOMADelaide, and Electric Avenue, Obongjayar will also perform headline shows at Sydney’s Metro Theatre and Melbourne’s Northcote Theatre.

The tour arrives on the heels of his bold second album Paradise Now - a technicolour dive into the mind of an artist at his creative peak. Shaped between London and Los Angeles with heavyweights Kwes Darko (Pa Salieu, John Glacier), Yeti Beats (Doja Cat), and Beach Noise (Kendrick Lamar, Baby Keem, Bakar), Paradise Now stretches the Obongjayar universe into new terrain. Pop, punk, dance, Afrobeat, funk, folk - all refracted through a dazzling, defiant lens.

This March, audiences across Australia and New Zealand will experience that vision in full force. The beauty is here. And Obongjayar has never sounded more present, more human, or more free.